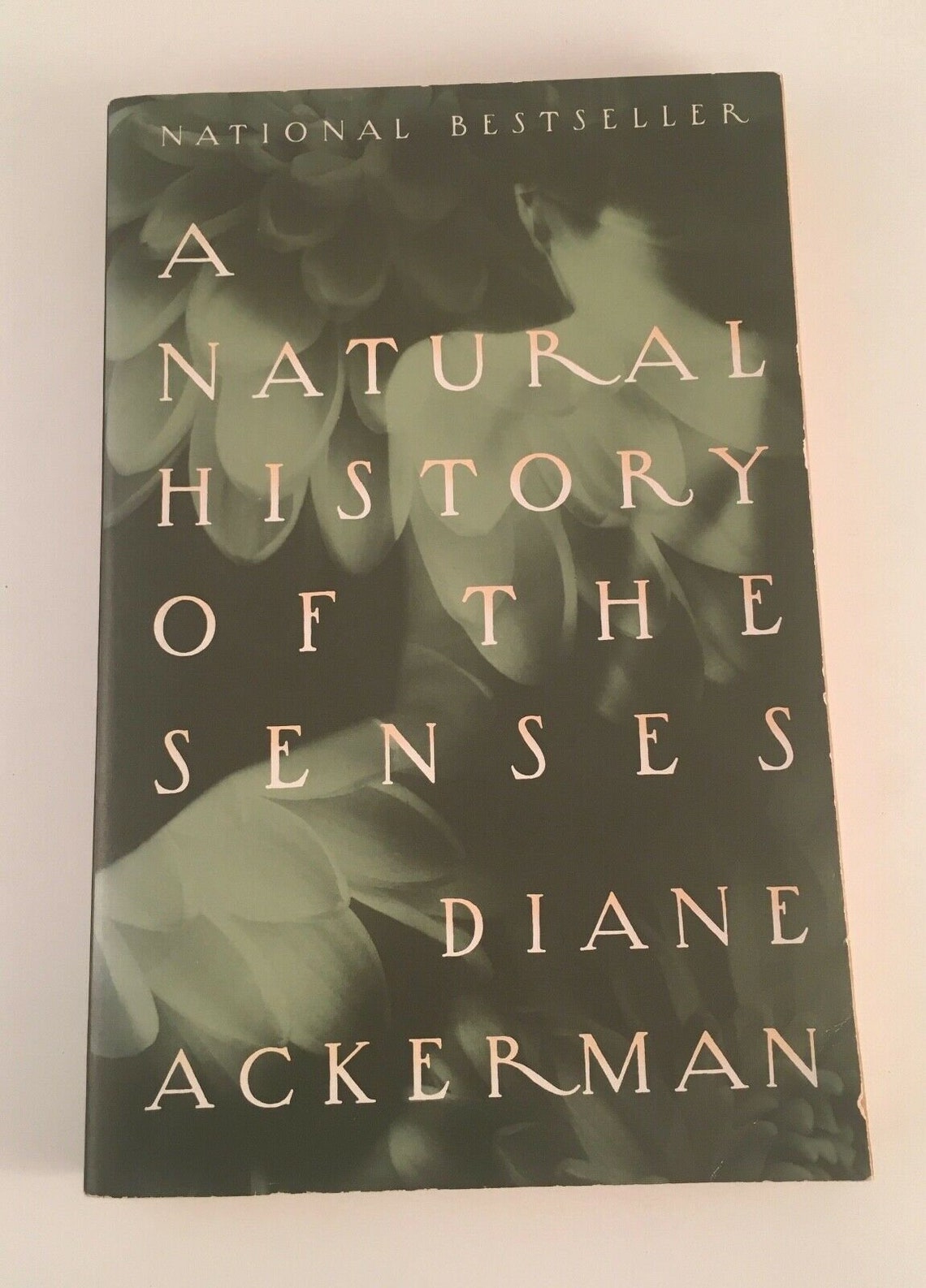

Our several senses, which feel so personal and impromptu, and seem at times to divorce us from other people, reach far beyond us. Ackerman writes:ĭeep down, we know our devotion to reality is just a marriage of convenience, and we leave it to the seers, the shamans, the ascetics, the religious teachers, the artists among us to reach a higher state of awareness, from which they transcend our rigorous but routinely analyzing senses and become closer to the raw experience of nature that pours into the unconscious, the world of dreams, the source of myth. One of William Blake etchings for John Milton’s Paradise Lost.Īckerman goes on to explore the biological machinery behind each of our senses as a function of consciousness and although the book is strewn with shimmering prose from cover to cover, it is in the closing pages that her sensibility rises toward Blake’s, folding the physical into the poetic in order to transcend it and enter the realm of the spiritual. The most distinguished chefs leave just enough of the poison in the flesh to make the diners’ lips tingle, so that they know how close they are coming to their mortality. In Japan, chefs offer the flesh of the puffer fish, or fugu, which is highly poisonous unless prepared with exquisite care. There is no way in which to understand the world without first detecting it through the radar-net of our senses… Our senses define the edge of consciousness, and because we are born explorers and questors after the unknown, we spend a lot of our lives pacing that windswept perimeter: We take drugs we go to circuses we tramp through jungles we listen to loud music we purchase exotic fragrances we pay hugely for culinary novelties, and are even willing to risk our lives to sample a new taste. That plurality is what science historian and poet Diane Ackerman explores with unparalleled elegance in A Natural History of the Senses ( public library) - her 1990 masterwork of science and poetics, which gave us the fascinating inner workings of smell. The same sliver of “reality” - a table, a flower, a city block - is experienced in a wholly different way by a bird, a dog, Blake, and you. Out of such seemingly simple discoveries across the animal kingdom sprang the rattling realization that our notion of “reality” is really a plurality of radically divergent impressions, shaped by the singular biases of perception that each of us brings to our experience of the world.

“How do you know but that every bird that cleaves the aerial way is not an immense world of delight closed to your senses five?” So marveled William Blake two centuries before we had the tools to confirm that, at the very least, every dog is a world of delight closed to our limited powers of sensorial perception.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)